Places Over Time: "Landmarks"

Jan 09, 2017

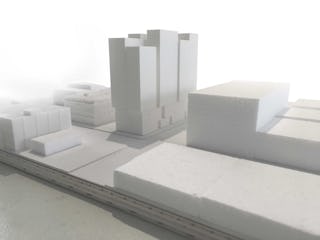

Image above: new Portland CEID project begins City Review.

The Architecture Design Blog "Places Over Time" published the article "Landmarks" discussing W.PAs influence on the Central Eastside Industrial District in Portland, Oregon.

Original Post https://placesovertime.wordpress.com/2016/12/27/landmarks/

"The Central Eastside has been the de facto testing ground for Works Progress Architecture since Strickland and Neburka’s partnership began a little over a decade ago. Having completed half a dozen new and renovated buildings in the area with almost as many more in the pipeline, Works has had and is having a huge impact in the area’s built environment. The firm’s projects have also helped define the architecture of this epoch, a localized architecture that continues to evolve with each and every new construction. In many ways WPA has always called this diffident district home, and the rapidly growing design firm’s yet-unfinished legacy is already having an undeniable impact in their own backyard.

Despite its appearance and provincial lore, the Central Eastside Industrial District has never been an unsuccessful place. The area has always adapted itself to the circumstances given to it, whether bad or worse, and has always been the unsung hero of the city so to speak. Portland has generally turned a blind eye to this prominently located neighborhood ever since it annexed it way back in 1891. The long-standing civic agreement was that the area would be purposefully restrained from development, allowing the hub of small businesses and light industrial practices to flourish as incubators before such a thing became an urban designer’s buzzword. Today, the Central Eastside is becoming Portland’s new center, a local’s downtown, as the streets of the traditional downtown across the river have become a place for tourists to mingle with the less fortunate and suburbanites to taste-test happy hour urbanism. The Central Eastside, on the other hand, has all the grit and charm of the working class bastion that it is, authentically cut off from nature by a Modernity-driven city council half a century ago and legitly dissected by age-old railroad ambitions, repressive concrete viaducts, and a lingering self-righteous attitude.

Works is currently undergoing design review for a new 13-story mixed-use building at 550 SE MLK, right in the heart of the Central Eastside and the old East Portland. The proposal includes residences and hotel uses above ground floor retail and underground parking. While the proposed design does not step too far from the design firm’s previous work in the neighborhood, the project’s typology is vastly different than its immediate surroundings. The recently completed Slate building also had residential uses, but that project was located along the Burnside-Couch corridor in the northernmost reaches of the CEID, a corridor that already had both residential and hotel precedents. The meat and bones of the Central Eastside is mostly devoid of residential and hotel uses currently, beyond the scattered pre-war apartments that were grandfathered in before the industrial sanctuary took hold. 550’s design looks more toward the distant past than the recent present, finding an urban form based more on East Portland’s oppidan remnants than those of the industrial warehouses that usurped it. The program itself is an expansion of the Hotel Chamberlain, Beam Development and Urban Development Partners revitalization effort of the old 1897 hotel building of the same name. Beam, UDP, and WPA have worked together before, and their long-term thinking has created some very interesting urban spaces over the course of the last few years.

550 SE MLK rests just outside of the East Portland Grand Avenue Historic District, which is fantastic, as the governing design review body will not have to be the Historic Landmarks Commission, who have been hellbent to make every new development a mockery of historic preservation. Just four blocks away, the HLC completely destroyed a viable and time-conscious project from Vallaster Corl, the Grand Belmont, and whittled their development team’s ambitions down to an Ankrom Moisan kitsch throwback that blurs the lines between historicism and disneyfication, similar to their nearby Goat Blocks project but with more soldier courses of brick veneer. In a decade or two, this watered-down faux-historic drivell will be mistaken for the real historic masonry buildings next door. This problem will continue as less than half of the historic district is actually historic buildings. This leaves more than half to be eventually redeveloped, redeveloped to the city’s Bureau of Planning and Sustainability, the Central Eastside Industrial Council, and Portland Streetcar’s goals of a high-density, high-rise neighborhood which is in direct opposition to the HLC’s obtuse goals of preservation through mimicry. 550 will not have to suffer the same fate, as its design will be reviewed by a group, the Portland Design Commission, that understands the importance of a cohesive urbanism and to respect the practice of architecture.

WPA’s latest proposal has some similarities to their other Beam and UDP project, the above mentioned Slate building, where the new tower is pulled away from an existing masonry building to create an alley-like retail space reminiscent of Old Town’s pocket plazas or older European dead-end streets. This simple move, coupled with the program requirements, drives the rest of the design: pushing the mass up instead of out, allows for unobstructed fenestration on all sides, creates a logic to the variations in the facade articulation, and directs interactivity in and out of its urban context. By being pushed away from its direct neighbor, the proposed building’s form is skinnier than traditional half-block towers, similar in height and width to Holst’s well-received 937 Condos. This also allows for the same amount of openings on all sides of the building, eliminating the need for fire related restrictions and allowing more light into the residences above. Additionally, the vertical porosity of the upper floors is broken where the internal program requires it, allowing for even more light to penetrate the residential floor plates. The first three floors of the proposal are treated as horizontal bands that directly relate to the internal hotel program while simultaneously acting as an homage to the cornice and pedestals of the adjacent brick structures. While a great deal of the architectural elements of the pre-war structures are based on stylistic principles, the base differentiation stems from the human scale experience, a scale that is absolutely paramount in the creation of vibrant urban spaces.

The alley is by far the most important element overall, as it splits the difference between the two automobile-centric streets, Grand and MLK, for the pedestrian. It also breaks the mold of the typical 200′ x 200′ development, allowing the public to delve into the private realm, creating intimacy and rapport. The alley is proposed to act as an external lobby for the hotel and residences, directly connecting the primary arteries of each building’s circulation systems instead of acting as a standalone, ambivalent amenity. Continuing the tangent on the Historic Landmarks Commission’s inability to honor architectural history, a similar ‘alley’ was approved by the HLC across the river at Ankrom Moisan’s 38 Davis, only to have its initial designs muted as being too contemporary (admittingly, relatively cheesy as well, but it at least had ‘character’). The now-complete building is another great example of faux-historic mimicry, but completely lacks any craft in its materiality and any elegance in its proportions and composition. Ankrom Moisan designed the building to be their new home, and their usual complacency toward mundane architecture allowed the HLC to walk all over their initial design intent. Even though 550 SE MLK’s alley is in the preliminary stages of development, it is already showing signs of being an intentional place rather than just extemporaneous space.

550 SE MLK continues WPA’s unrelenting sense of experimentation, exploring the idea of a contemporary East Portland building. As the Central Eastside Industrial District fills in with the next generation of employment and urban living, there will be more and more pushback from those who dislike the changes. This is all the more reason to advance a higher standard of architecture, an architecture that promotes the way we live and work and play today, rather than obsess with the perception that a bygone method of construction translates into better design. At the north end of the CEID, a mix of new towers and low-rises are advancing this theory along Burnside, some with generically humble intents and others who want to investigative a more ambitious paradigm. The central part of the Central Eastside has yet to see any dynamic new architecture, and perhaps all it takes is a precedent setter to get things going. Perhaps 550 will be such a design, or maybe it won’t. No matter, as long as Portland’s more innovative design firms continue to best their less ambitious counterparts, the local built environment will just keep getting better and better."